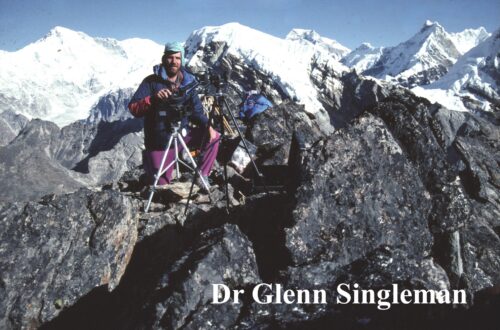

Dr Glenn Singleman:

I first met Chris Dewhirst in March 1990, when he called asking if I could build him a reliable oxygen system that would work in a balloon at 35,000 feet. He also asked if I knew any sky-divers, and could I film at minus 50 degrees Celsius.

‘Happy to sort out your oxygen, and yes I know a sky-diver, or two, and I’ve filmed colder than minus 50 degrees.’

‘Excellent,’ he said. ‘I need to drop 100 kg from high altitude to see how a balloon might perform above Mt Everest–Chomolungma–if I need to throw out ballast, in turbulence,’ which is how I came to film an Australian sky-diving balloon altitude record, while dangling from a rope attached to the top of the balloon. Chris is one of the few people in the world who would think this a good idea–so of course we bonded right away.

Chris and I have shared multiple adventures and both of us have a passion for aviation. We’ve also shared meals, glasses of red wine and many, many great stories. Despite all that, Chris has never shared the story that follows–perhaps the wildest one of all. On first reading I was gobsmacked, riveted, captivated, stunned, and incredulous. I missed meals and sleep because I couldn’t stop reading this unbeknownst dark-chapter in the life of one of Australia’s most decorated aviators and extreme climbers.

Why we do such things is worth exploring. The answers are complex: metaphysical, genetic, and occasionally something else entirely–as Chris explains in Everest, Guns & Money. However, Chris, and many of our mutual friends, undertake extreme adventures to explore ourselves both physically and psychologically. Climbing the impossible, kayaking grade 6 rapids on the Franklin River, flying a balloon over Mt Everest, base-jumping from the world’s tallest cliff, and diving the deepest canyons, connects us to nature and creates friendships that last forever.

Years of bold, wilderness experience forged Chris’ character: strong, resourceful, capable, decisive and calm. So, when I needed help training my wife, Heather Swan, to BASEjump, by first leaping from a hot air balloon, he was the one that I most trusted to pilot the aircraft.

Heather and I wanted to break my existing world record–5962m–for high altitude BASE jumping, and the safest way to learn was from a balloon. I vividly remember our last training jump near Canowindra in NSW–just before leaving to climb the Great Trango Tower in Pakistan–when Chris warned us there was a fast wind developing at higher altitude, although the all-important wind on the ground would likely remain good for our landing. At jump height, the wind had increased to 50 knots, and we were soon overtaking the traffic, a mile below. Remarkably, standing in the balloon was calm and windless.

Unaware of the developing problem, our team were faffing around with the details of jumping and filming. We were fully focussed on what we were doing and oblivious to the ground speed – and the limited time available to make the jump. Chris’s voice cut through the chatter like a knife: ‘It’s time to leave. We’re heading for a forest with no landing areas. I want these parachutists out of my balloon, NOW.’ In the sudden silence, everyone turned to look at Chris. He had that: ‘I’m not fucking around,’ wild eyed glare. And I thought: this is what Mr Unflappable looks like when he’s rattled.

‘We’ll be gone in 30 seconds,’ I said. And we were.

Adventurers like Chris and I are often asked why would anyone take such risks? The throw-away line – because we can – is the glib answer, allowing us to move onto other topics. However, as a lecturer in Extreme Sport Medicine, I don’t do glib. Finding an explanation has been the basis of my academic career for decades. In my experience, no one asks why as they’re hurtling down a rollercoaster. Most of us just hang on and scream, then feel elated when we survive. We seldom wonder at the motivation, or ask what was behind those feelings of exhilaration. And few of us ever think to ask what it might say about the human condition. Why is it that we build artificial thrill machines, or sometimes risk death pushing the boundaries of existence in the natural environment? Perhaps Abraham Maslow’s hierarchy of needs, with ‘self-actualisation’ at the top, explains the adventurer’s motivation. However, more recently, genetics has been found to play a direct part in the desire to extend the limits of what’s possible.

Does Chris, and his like-minded friends, possess the maximum number of the so-called thrill-seeking gene (11 copies of the polymorphic DRD4 gene on chromosome 11)? Probably. Does Chris have insensitive dopamine receptors in his brain that require maximum stimulation to achieve the ‘feel good’ effect of the neurotransmitter? Probably. And does any of this matter in what you are about to read? Probably not. This book will take you on a wild ride – a metaphorical roller coaster and leave you on a high – but it will also make you wonder about the moral compass of a society that sends its youth into extremis.

The following stories document the essence of a man who has lived life to the fullest, seized the day and turned the volume up to 11.