CHAPTER 1: The Philosopher’s Table.

The Salathé Wall on El Capitan, and the Northwest Face of Half Dome, in 1973, were widely recognised as two of the most spectacular climbs on the planet.

They still are: think Alex Honnold and Free Solo.

Royal Robbins, who made the first ascent of both, in the 1960s, became a rock-climbing legend. He named his route on El Cap after climbing pioneer and blacksmith, John Salathé, who created the chrome vanadium piton, called the Lost Arrow. In the early years, before chocks and cams were invented, a hardened piton was necessary protection for an unyielding Yosemite granite.

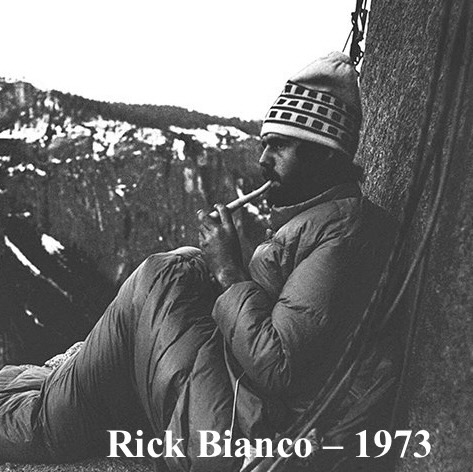

Carrying a few Lost Arrows, and plenty of chocks, at the end of our second day on the Salathé Wall, Rick Bianco and I, squeezed ourselves onto the Block, a small ledge 2,500 feet above the giant redwoods, eight pitches from the top.

‘It’s short for blockhead,’ said Rick. ‘Like most of the rangers down there.’

‘That’s cruel,’ I said. ‘They’re probably just misunderstood, like Officer Krupke.’

‘West Side Story. The Jets,’ he said. ‘But I’m telling you, they’re mafia in uniform. When they come for your park permit at midnight, you’ll change your tune. Anyway, we need to upgrade the name, and I’m calling it The Philosopher’s Table in honour of Timothy Leary’s latest discourse on the inevitable corruptibility of a uniform.’

Rick Bianco, known to his many friends as RB, had developed an allergy to uniforms after the 1970 Yosemite riots when rangers on horseback violently dispersed a peaceful, but noisy fourth of July party. It was complicated, although Rick, who had no time for tyrants, thought otherwise.

‘What about nurses, they wear uniforms?’ I asked.

‘That was remiss of me, I should have asked that question.’

‘Once a year nurses turn up in Australian schools vaccinating the reluctant,’ I said, continuing our conversation from the previous night about why he had a withered left leg. ‘If you were last in line the needle bent.

‘Unfortunately, Dad didn’t believe in polio, only punishment.’

‘Then he must have believed in Charles Darwin,’ I said, handing him the joint.

‘God’s punishment I should have said. He was more Noah’s Ark than Charles Darwin. After Dad ran off with his secretary, mom couldn’t get Jesus off the wall fast enough. Where we grew up that was wild. Mom was an antichrist at heart with no time for cripples. And with seven kids at home, it was law of the jungle. Think Planet of the Apes.’

He leaned back against the cold granite wall, sucked in a lungful of Mexican Gold, and then handed the joint to me. The sleeve of his tartan jacket flapped in the wind.

‘Is that one of those shirts Chouinard sells from the back of his van?’ I asked.

‘It’s state-of-the-art fabric. It kept me alive last year on Mount McKinley.’

‘Winter wool from Scottish sheep. That’s Chouinard’s secret. You don’t need a Norwegian goose-down jacket when you have an authentic Macbeth.’

‘Lay on with sheep Macduff! Don’t you hate getting out of a sleeping bag to have a leak?’ he said, standing up, checking that he was still tied onto the belay peg. ‘I may be some time.’

After two days on the wall–I may be some time–was a question, not a statement. He lent into the void and relieved himself.

‘Captain Oates, the first Anglo-Saxon snow-walker!’ I said, referring to Captain Scott’s ill-fated expedition to the South Pole when Oates deliberately walked off into a blizzard.

‘Very good. I didn’t expect you’d get that one. The British love heroic failure. After Scott, there was Mallory on Everest and all those stupid African explorers. Mind you, they were excellent at colonising, and war, but we booted them out of the USA. Taxation without representation wasn’t the full story.’

‘Follow the money,’ I said, quoting Bob Woodward from the Washington Post, investigating the Watergate break-in.

‘You’re right there, but it wasn’t about taxation. It was mostly about the abolition of slavery. However, slaves don’t get paid. And if you’re a running-dog capitalist it doesn’t get better than that.

He worked his sleeping bag up over his shoulders. His head rested on a bag of peanuts.

‘Why do climbers carry chalk bags?’

‘That’s rhetorical. Surely?’ I said, but it was another one of RB’s puzzles.

‘Before every move we dip into our bag–left hand, right hand–chalking the granite in silent benediction. El Capitan is nature’s altar, and we are its high priests–reverends of the vertical–on a stairway to heaven….’

‘Led Zeppelin!’

‘I knew you’d get that one,’ he said, popping the last beer, and handing it to me. ‘There’s no point hauling this to the top tomorrow.’

I took a swig and handed it back.

‘What made you take up climbing?’ he asked.

‘When I was 12 I hung a poster of Half Dome, by Ansel Adams.’ And Australia didn’t allow bullfighting.’

‘That’s a coincidence, I hung the same poster. You know, we have bull fighting in those Texas rodeos, which is an absurd remnant of the Roman Colosseum.’

He flourished his woollen hat, pretending to be a matador. The wind snatched it from his grasp, and it flew off into the night.

‘Shit. That was my favourite.’

‘I’ve got a spare,’ I said, handing him my Mount Cook beanie.

‘That’s very generous. Tell me about fighting the bulls.’

‘When we were kids I strapped sharpened sticks to a cross-piece, attached to a wheelbarrow. John Moore, my school buddy and I took turns being the bull, or El Cordobés, until I skewered him attempting a Verónica. It was blood on the sand, like Hemingway. After that we read The White Spider on climbing the North Face of the Eiger.’

‘Hemingway–literature’s Muhammad Ali–where every sentence is a knockout–but Death in the Afternoon should be banned–and The White Spider, for that matter. Adventure pornography should be sold under the counter. It leads youngsters astray,’ he said, rummaging through the haul bag for more food. ‘Shit, I forgot the pie. You can blame Morabito for that.’

‘Who’s Morabito?’ I asked.

‘Frank the blade Morabito heads up Yosemite National Parks.’

‘Why the blade?’

‘He takes a cut of everything going. If you want a licence to sell ice cream in the Park, then Morabito takes his ten percent.’

‘Whoa… How did he get the top job?’ I asked.

‘He escaped from Cuba after double-crossing Castro. He found someone well-placed in the US embassy in Panama, where he swapped information for US citizenship and a job. It had something to do with the Cuban missile crisis, nuclear weapons and assassinating the Kennedy’s.’

‘Seriously. The Kennedy’s?’

‘The CIA set up that young Mexican kid to kill Bobby Kennedy. They use hypnosis to make people do their dirty work. I have it on the best authority that Harvard University designed the program.’

‘That’s hard to believe,’ I said, thinking that RB was into excellent conspiracy theories. A few months later I found out that he was very close to the truth. ‘Can hypnosis do that sort of thing?’

‘You’d better believe it. Mike, my evil brother, runs the CIA. Well, anyway, he’s at the front desk, and unless you’re nice to him, he won’t let you pass. I hear all the family gossip. The Kennedy’s fucked over the generals, who wanted to nuke Russia and China during the missile crisis. The assassinations were pay-back. Everyone knows that the CIA murdered JFK. And his little brother. But now Nixon’s in power the generals get their way.’

‘Nixon answers to the military? It should be the other way around.’

‘The generals like the big bombs, and I think Nixon will nuke Hanoi any day now. It won’t be pretty. But this is the perfect place to be when the Russians retaliate. Our bodies will be shades forever imprinted onto God’s granite.’

‘Hopefully, etched onto the headwall,’ I said, visualising a chalk outline drawn by the coroner, my head spinning at the thought.

‘The headwall! It’s amazing to go where no one has gone before. It’s when legends are made and written into the universal consciousness. Busts of Meyers, Chouinard, Bridwell and Robbins should be carved into the headwall, like those Presidents on Mount Rushmore.’

‘That would be a big job on this granite, even for Michelangelo,’ I said. ‘How about sculpting Zion National Park instead? It’s made from sandstone.’

‘We should do some climbing in Zion. I’ve never been there,’ he said, sucking hard on the joint, holding in the smoke longer than I thought possible. ‘It’s a four-dimensional world up here. This is where we find absolution. And maybe God, although I think my mom is right about God. I don’t know any religious climbers.’

RB finally fell asleep. After swinging leads for twenty-eight pitches, I was over the horror of watching him use a free hand to position his lame foot on a hold. At that convoluted moment, it seemed a miracle that he remained attached to the wall at all. He was awkward and bumbled one moment, like a pelican taking flight–all splash, dash and despair–but beautiful the next, as it all came together.

The village searchlights came on–flashing red and blue, illuminating the ancient sequoias–brightly enough to make Neil Armstrong think he was speeding. Lego vehicles rolled from the Ahwahnee hotel car park, while Lego people strutted about, avoiding the Lego bears that foraged through the rubbish bins. Yosemite’s big wall music rendered all things lilliputian.

I lay back on the block using my friction shoes as a pillow, tied to a piton. Having lost a shoe during the night on the north wall of the Buffalo Gorge, a few years earlier, on a climb called Führer that I’d soloed–and having to complete the climb one foot bare, in ice and snow, I was determined that was never going to happen again.

I was looking forward to climbing the last few pitches on the headwall, imagining my spreadeagled shadow imprinted on the granite by a retaliatory Russian hydrogen bomb, when I heard an aircraft in trouble. One of its two engines spluttered and stopped, a radial piston engine, and not a whining turbine. It seemed very close, although it was out of view, somewhere above El Cap, but with only one working engine, the only direction was down. Where could he land in the Sierra Nevada and survive? It didn’t bear thinking about. I heard no more, and pondering the likely outcome, I fell asleep, dreaming of Armageddon.